it is important to recognize that real GDP is an analytic concept. Despite the name, real GDP is not “real” in the sense that it can, even in principle, be observed or collected directly, in the same sense that current-dollar GDP cannot in principle be observed or collected as the sum of actual spending on final goods and services in the economy. Quantities of apples and oranges can in principle be collected, but they cannot be added to obtain the total quantity of ‘fruit’ output in the economy—Steven Landefeld and Robert P. Parker, Bureau of Economic Analysis, 1995

In this issue

Q3 2024 5.2% GDP: Consumers Struggle Amid Financial Loosening, PSEi 30 Deviates from the GDP’s Trajectory

I. The PSEi 30 Deviated from GDP’s Trajectory

II. The Treasury Markets as a Harbinger of the Economic Slowdown

III. Lessons from the 2024 US Elections: Markets Overwhelm Surveys

IV. GDP: A Tool for Political Narrative

V. The GDP Trend Line in Context: Insights from SWS Self-Poverty and Hunger Surveys

VI. Q3’s GDP Story: Consumer Spending Rebounds on Declining Inflation and Lower Rates

VII. Consumers Struggle Amid Rising Employment and Vigorous Bank Credit Expansion

VIII. Lethargic Q3 2024 Sales of Wilcon and Robinsons Retail Challenge the Consumer Rebound Narrative

IX. Public Spending Segment of the Marcos-nomics Stimulus: Are Authorities Pulling Back?

Q3 2024 5.2% GDP: Consumers Struggle Amid Financial Loosening, PSEi 30 Deviates from the GDP’s Trajectory

Despite declining inflation rates and lower interest rates, Philippine consumers face tremendous obstacles, as shown by the 5.2% Q3 GDP growth. The PSEi 30 has mispriced the GDP's trajectory

Reuters, November 7, 2024: The Philippine economy grew in the third quarter at its slowest annual pace in more than a year as severe weather disrupted government spending and dampened farm output, to strengthen the case for further policy easing. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew 5.2% in the July-September on the year, government data showed on Thursday, below a Reuters poll forecast of 5.7%, for the most tepid rise since expansion of 4.3% in the second quarter of 2023.

I. The PSEi 30 Deviated from GDP’s Trajectory

Stock markets are often considered discounting mechanisms for future economic activity. But are they?

The PSEi 30’s impressive 13.4% return in Q3 2024—the best since 2010—was largely based on expectations that low interest rates would stimulate economic activity.

However, despite the BSP’s rate cut in August 2024 and the tacit Marcos-nomics stimulus, Q3 GDP fell to its lowest level since the 4.3% recorded in Q2 2023.

Figure 1

Viewed in the context of the 15% year-over-year returns at the end of last Q3, the PSEi 30 has moved in the opposite direction to the GDP. (Figure 1, topmost graph)

Faced with this inconvenient reality, the PSEi plunged 2.32% this week, marking its third consecutive weekly decline and dipping below the 7,000 level—a 7.6% drop from the October 7th peak of 7,554.7.

Interestingly, a local media outlet, still grappling with "Trump Derangement Syndrome," attributed this decline to Trump's electoral victory, suggesting that local stocks "price in the risks of a second Donald Trump presidency and an economic slowdown."

If the "Trump trade" holds any truth, not only did US stocks soar to new records, but Asian equities also saw significant boosts this week. Among the region's 19 national benchmarks, 14 recorded positive returns with an average gain of 1.33%!

The exceptions were Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, India, and Sri Lanka. How does this fit into the narrative of the "Trump trade"?

Moreover, it's not just the PSEi 30 that should raise our concerns. Given that the financial sector has been a market leader, the financial index also warrants close attention.

The financial index posted a remarkable 23.4% year-on-year return at the end of Q3 2024, despite a notable deceleration in the sector's GDP since its peak in Q4 2023. The sector recorded an 8.8% real GDP growth in Q3, up from 8% in Q2, but lower than the 12% and 10.3% growth in Q4 2023 and Q1 2024, respectively. Bank-led financials have been a critical source of gains, as evidenced by their increasing share of the sector's GDP, despite the 2022-2023 rate hikes. (Figure 1, middle and lowest images)

Led by banks, the financial sector is the most interconnected with the local economy. Its health is contingent or dependent upon the activities of its non-financial counterparties.

Alternatively, the sector’s outgrowth relies on political subsidies and is subject to diminishing returns.

Yet ultimately, this should reflect on its core operational fundamentals of lending and investing.

This week, the financial index fell by 2.9%. As previously mentioned, trading activities in the PSE have been heavily skewed toward this sector.

In essence, the divergence between the PSEi 30 and GDP illustrates the significant market dislocations caused by the allure and regime of easy money—a quest for something for nothing.

II. The Treasury Markets as a Harbinger of the Economic Slowdown

Figure 2

As we have repeatedly pointed out, the Philippine Treasury markets have long been signaling an economic slowdown. The steep slope observed in Q1 has shifted to a bearish flattening and, subsequently, an inversion of the "belly," suggesting a further deceleration in inflation and a downshift in economic activity. (Figure 2, topmost diagram)

Experts have rarely discussed how the declining inflation reflects a downturn in demand. However, this scenario was evident across the entire Treasury curve in 2024, which explains the sharp plunge in T-bill rates and increased expectations that the BSP would cut rates. The BSP responded by implementing cuts in both August and October.

III. Lessons from the 2024 US Elections: Markets Overwhelm Surveys

The 2024 U.S. elections provided a striking illustration of the comparative efficiency between markets and surveys.

As pointed out above, markets are imperfect, but most of their vulnerabilities stem from underlying interventions that enhance them. However, when people place bets to prove their beliefs or convictions, they demonstrate "skin in the game""—a vested interest in success through real-world actions or "having a shared risk when taking a major decision."

In contrast, individuals can express opinions they do not genuinely believe. Numerous factors—such as assumptions, coverage, inputs, delivery, and measurement—contribute to errors in surveys. Worse still, surveys can be designed to achieve specific outcomes rather than accurately estimate reality.

Using the last week’s elections, the average betting odds from several prediction markets, led by the largest platform, Polymarket, indicated that Trump would win by a landslide going into the election. (Figure 2, lowest chart)

This was contrary to the average polls, which showed a razor-thin edge for Democratic candidate Kamala Harris. Interestingly, similar to the 2016 elections, these polling discrepancies were exposed only after Trump’s victory. (Figure 2, middle table)

By sweeping all the battleground or swing states, Trump secured an electoral landslide winning 301 to 226 (according to The New York Times) and also became the first Republican to win the popular vote since George W. Bush in 2004.

This experience reaffirmed that markets have proven to be more reliable than surveys. And this reliability extends beyond elections to broader economic metrics, exposing vulnerabilities even in government data (such as inflation, labor statistics, and GDP).

Although designed to be objective and systematic—where hard and verifiable transactional records form part of the government’s comprehensive data—a significant portion still relies on self-reported or opinion-based data.

These components introduce the potential for bias and inaccuracies.

More importantly, as a political institution, government data is not only susceptible to errors but can also be engineered to advance the agenda of the incumbent government.

One way to countercheck the reliability of these data points is through the logic of entwined data—the idea that when multiple, independent data sets or sources are connected, discrepancies or patterns can be identified. By cross-referencing market data, surveys, and government statistics, we can better assess the accuracy of any single dataset. The entwinement of data from diverse sources can serve as a powerful validation tool, especially when inconsistencies or contradictions emerge.

Thus, comprehensiveness, large scale, and systematic nature of government data collection do not make it foolproof from errors caused by either interventions or design.

IV. GDP: A Tool for Political Narrative

The establishment has promoted GDP as an estimation of economic well-being, but that’s only a segment of the entire spectrum.

Unknown to the public, GDP is primarily a political tool.

In the 1660s, William Petty conceived GDP as a means to estimate war financing during the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

Under the influence of John Maynard Keynes, it was further used to promote wartime planning during World War II, which eventually evolved into—or became the foundation of—modern macroeconomic policy (Coyle, 2014).

Simon Kuznets, a pivotal figure in the development of modern GDP, famously cautioned that "economic welfare cannot be adequately measured unless the personal distribution of income is known… The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined above." (bold added) [Wikipedia, GDP]

This statement underscores the limitations of GDP as a comprehensive measure of economic well-being.

In 1962, Kuznets further emphasized the need for clarity in economic growth metrics, stating: "Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what."

This highlights his belief that economic indicators should reflect not just output but also the broader implications of growth on society.

Applied to the current developments…

The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), citing the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs as the source for their adaptation of the System of National Accounts (SNA), noted that "GDP is used to evaluate the overall performance of the economy and, hence, to judge the relative success or failure of economic policies pursued by governments." (bold added) [unstats, 2009]

The embedded assumption is that a factory GDP—or a top-down model—drives the economy.

But if that’s the case, then some questions arise:

-Why doesn’t the Soviet Union still exist?

-Why do black markets or informal economies emerge or thrive in heavily regulated economies?

-Does the government dictate to Jollibee or SM who they should sell to?

Yet, aside from gaining popular approval for election purposes, the contemporaneous implicit goal of GDP growth could be related to ease of accessing public savings to fund government expenditures.

V. The GDP Trend Line in Context: Insights from SWS Self-Poverty and Hunger Surveys

Still, there are many ways to "skin"—or analyze—the GDP "cat."

Although GDP is presented as a year-over-year (YoY) change predicated on a base effect, a very significant but largely ignored fact is its trendline.

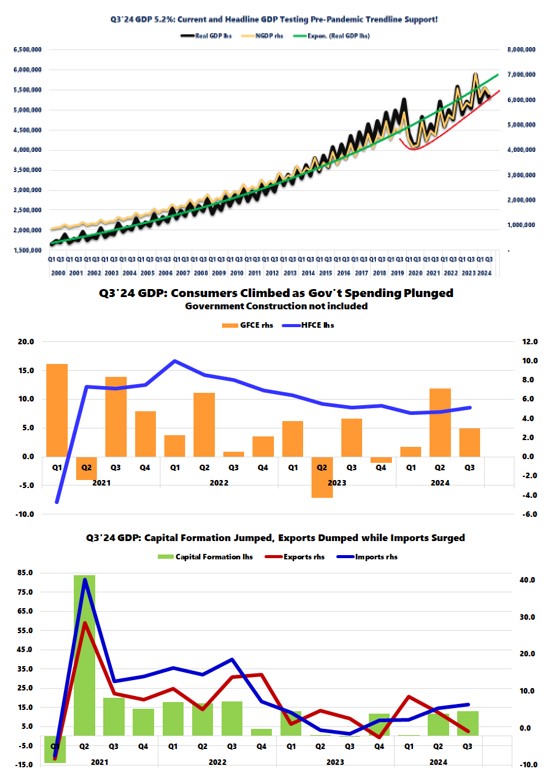

Figure 3

Fundamentally, despite all the media and establishment cheerleading—particularly with the emphasis on achieving an upper-middle-income economy—both nominal and real GDP have been performing below their pre-pandemic trendlines. (Figure 3, topmost diagram)

Worse, the Q3 GDP growth of 5.2% is sitting precariously on the support level of a subsidiary trendline, suggesting it may be testing this support. What happens if it breaks?

Additionally, what about the recent SWS Q3 2024 surveys exhibiting self-poverty ratings at 2008 highs, and hunger incidence reaching its second highest level since September 2020, during the pandemic recession? (see our previous discussion here)

Has the SWS survey been validated?

As a side note, the left-leaning OCTA Research group's Q3 survey results were starkly different from those of the SWS.

Have the authorities made a partial concession to the SWS findings by revising down the GDP growth estimates?

As a reminder, polls or surveys—whether conducted by the private sector or the government—are opinion-based or self-reported data and are inherently prone to errors.

VI. Q3’s GDP Story: Consumer Spending Rebounds on Declining Inflation and Lower Rates

GDP is not just about the numbers; it has been crafted to tell a story.

Essentially, it follows the mainstream’s logic: slowing inflation and lower interest rates would boost consumption and, consequently, GDP.

Well, that is how the Q3 5.2% GDP played out.

From the expenditure side of GDP, real household consumption increased from 4.7% in Q2 to 5.1% in Q3, thereby boosting its share from 67.7% to 72.8%. (Figure 3, middle image)

In contrast, government spending on GDP dropped significantly, from 11.9% in Q2 to 5% in Q3, reducing its share from 17% to 14.7% during the same period.

Meanwhile, due a slump in government activities, construction GDP growth nearly halved from 16.2% to 8.9%, diminishing its share from 19.4% to 14.1%. Government construction GDP tumbled from 21.7% to 3.7%.

Thanks to increases in machinery, transport, and miscellaneous equipment, durable equipment GDP surged from a contraction of 4.5% in Q2 to growth of 8.1% in Q3. (Figure 3, lowest visual)

Nevertheless, exports plummeted from 4.2% in Q2 to a shrinkage of 1% in Q3, while imports increased from 5.3% to 6.4%. The widened gap in favor of imports—net exports—contributed to the slowdown of GDP.

This summarizes the expenditure-based GDP analysis.

VII. Consumers Struggle Amid Rising Employment and Vigorous Bank Credit Expansion

Circling back to consumers: considering that the Philippine economy has allegedly reached near-record employment levels (close to full employment), why does consumer per capita growth continue to struggle?

Figure 4

The employment rate hit 96.3% in September, yet Q3 household per capita growth increased only slightly, from 3.8% to 4.2%—the third lowest growth rate since Q2 2021. (Figure 4, topmost window)

Additionally, what explains the consumers' ongoing challenges in light of Universal-commercial bank lending, which reached a record high in nominal terms and grew by 11.33% in Q3—the highest rate since Q4 2022? This growth was notably powered by household credit, which also surged by 23.44%, although it was down from its peak of 25.4% in Q1 2024. (Figure 4, middle graph)

On a related note, even though the money supply (M3) hit a record of Php 17.58 trillion in Q3, its growth rate of 5.4% was the lowest since Q3 2022.

Despite the crescendoing systemic leverage (public debt plus bank credit expansion), which grew by 11.4%—the highest since Q4 2024—to a record Php 27.97 trillion, why has the money supply been trending downward?

Moreover, as evidence of the redistribution effects of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) policies favoring banks amidst the thrust towards financialization, various money supply metrics (M1, M2, and M3) relative to GDP remain at pre-pandemic levels in Q3 2024, despite having clawed back some gains from the 2021 milestone. (Figure 4, lowest chart)

Despite all this, the persistent challenges of consumers continue.

Yet, this raises a crucial point: the GDP appears increasingly dependent on money supply growth and credit expansion.

VIII. Lethargic Q3 2024 Sales of Wilcon and Robinsons Retail Challenge the Consumer Rebound Narrative

There’s more.

Figure 5

In the face of a slow recovery in consumption, retail GDP dropped from 5.8% in Q2 to 5.2% in Q3 2024. (Figure 5, topmost image)

Oddly, bank lending to the sector has been soaring; it was up 12% in September from 9.3% last June.

Where is the money being borrowed by the sector being spent?

Meanwhile, Household GDP figures might be inflated.

Two major retail chains operating in different sectors have reported stagnation in topline performance.

Despite expanding its stores by 12% year-over-year (YoY), the largest downstream real estate consumer chain, Wilcon Depot [PSE: WLCON], experienced a 3.35% YoY contraction in sales and a 4.35% decline quarter-over-quarter (QoQ). (Figure 5, middle graph)

The company's worsening sales conditions have partially reflected the plunge in the sector’s Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Similarly, Robinsons Retail [PSE: RRHI], one of the largest multi-format retailers, reported another lethargic topline performance. (Figure 5, lowest chart)

In Q3, the firm’s sales increased by 3.13%, primarily driven by its food segment (supermarkets and convenience stores), which grew by 4.8%, along with drug stores, which increased by 9%.

However, three of its other five segments—including department stores, DIY, and specialty—suffered sales contractions.

Taking into account that the sales from these two retail chains constitute a portion of nominal GDP, applying the GDP deflator would indicate a deeper decline in WLCON's sales and flat sales growth for RRHI.

Despite the slowdown in inflation and the rapid growth in consumer bank borrowings, consumer spending has gravitated toward essentials (food and drugs) while reducing purchases of non-essentials.

This observation lends credence to the recent Social Weather Stations (SWS) self-poverty ratings.

So far, despite loose financial conditions, the performance of these two retail chains contradicts the notion embedded in GDP that consumers have partly opened their wallets in Q3.

For a clearer picture of consumer health, we await the financial reports of the largest retail chain, SM, and other major goods and food retail chains.

Imagine the potential impact of real tightening conditions on consumer spending and GDP!

IX. Public Spending Segment of the Marcos-nomics Stimulus: Are Authorities Pulling Back?

Recent GDP data suggests a slowdown in public spending, but a closer look reveals a different narrative.

While overall public spending growth has declined, sectors heavily influenced by the government are seeing gains.

Specifically, public administration and defense GDP rose from 1.8% in Q2 to 3.7% in Q3. Similarly, sectors with significant government involvement, such as education and health, reported growths from 1.9% to 2.6% and 9.4% to 11.9%, respectively.

Despite the appearance of a slowdown, the bureaucracy and government-exposed sectors continued to show growth.

That’s not all.

Figure 6

According to the Bureau of Treasury’s cash operations report, the Q3 expenditure-to-GDP ratio remains at a pandemic-level rate of 24%.

Additionally, although tax revenues improved, the Q3 deficit-to-GDP increased from 5.3% to 5.7%, again reflecting pandemic-level deficits.

It’s essential to note that the treasury data and the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) GDP figures—which include their calculation of public spending—represent an apples-to-oranges comparison.

However, we can still glean insights from a historical perspective of the Treasury’s activities.

So, why do current data sets indicate sustained increases despite the perceived temperance in government spending?

While authorities may embellish their deficit data, the consequences are likely to manifest elsewhere.

Aside from the counterparties that provide financing via debt, it will manifest in the trade balance and eventually impact the private economy—via consumers: the crowding-out effect.

Q3 Public debt stands at 61.3% of the sum of the last 4 quarters (Q4 2023 to Q3 2024)

Thus, it’s not surprising that Q3’s fiscal deficit coincided with a notable spike in the trade deficit, which ranks as the fourth highest on record.

The existence of "twin deficits" points to excessive spending and reveals a historic savings-investment gap that necessitates record borrowing through debt issuance and central bank interventions.

Adding to this context, the massive RRR cut and BSP’s second round cut of 25 basis points all took effect this October or in the fourth quarter.

We can also expect the government to aim to accomplish its end-of-year spending targets in December, adding to this period’s fiscal activity.

This implies that the full impact of the 2024 "Marcos-nomics" stimulus implemented in Q4 could result in a short-term GDP boost but at a substantial cost to the private sector economy.

___

references

Steven Landefeld and Robert P. Parker, Preview of the Comprehensive Revision of the National Income and Product Accounts: BEA’s New Featured Measures of Output and Prices, Bureau of Economic Analysis, 1995

Diana Coyle, Warfare and the Invention of GDP, the Globalist, April 6, 2014

Wikipedia, Gross Domestic Product, Limitations at introduction

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, System of National Accounts 2008, 2009, p. 4-5 https://unstats.un.org/

No comments:

Post a Comment